Marianne Cramer

Job Title: ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR

Contact

Email: mcramer@uga.eduPhone: 706-542-7112

Street address: 107 Denmark Hall

Athens, GA 30602-1845

Personal Interests

Drawing and SketchingGuerilla Gardening

Marianne Cramer

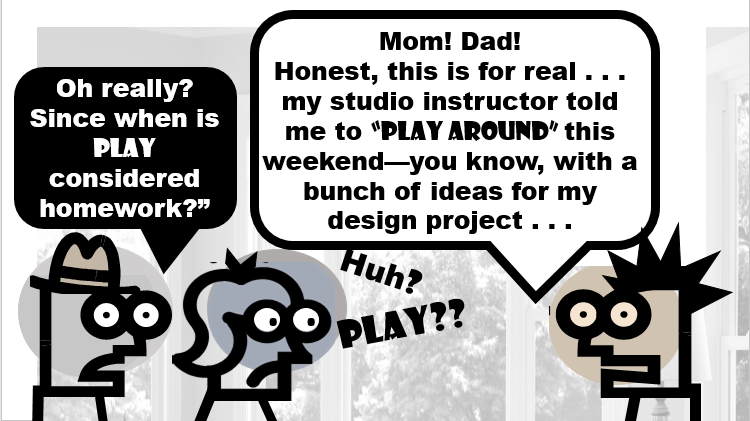

THE IMPORTANCE OF PLAY IN THE DESIGN STUDIO

Most of us assume play is for children. If adults play around it is more likely considered a waste of time, especially when the work clock is ticking. However, people of all ages engage in play—creative storytelling around a campfire; building houses out of piles of autumn leaves; sneaking pots and pans out of the kitchen to do something more interesting than boiling water. And if we are honest with ourselves, we do play at work and play with our work, sometimes with amazing results.

What good is play? Authors Robert and Michele Root-Bernstein consider play one of the 13 thinking tools of the world’s most creative people (1999). Resnick (2017, 128) refers to play as one of the four P’s of creative learning and believes that playfulness is more important than play. When we are playing around we engage our imaginations—the wellspring of creativity, experiment with possibilities—some of them totally wild and crazy, take risks that we might not normally take in a more restrictive environment, and discover unlikely directions to explore further. Playing around the pressure is off, and all of a sudden we can have fun!

Play in the studio is purposeful. Since design is project based, a written brief creates boundaries for a specific project most often accompanied with a set of requirements. Within that space are an unknown number of possibilities. Play is a way to explore them. In the studio asking the ‘What if?’ questions or wondering ‘What might be?’ are playful prompts that take designers beyond an easy standard response. Sometimes playing around is as simple as turning an image upside down or scattering left-over pieces of a project to see what happens. Play is in many instances about serendipity.

Learning in the studio is less about direct instruction and more about learning by doing. As designers, we make things; making engages both the mind and the body, what psychologists call embodied cognition. Being encouraged to play situates exploring and testing ideas in a nonthreatening environment; if an idea doesn’t quite work out, it is still an important learning opportunity. The importance of looking at a range of possibilities cannot be overstated. Design is not about getting it right the first time. In our hyper test-taking world we are programmed to look at every situation where an answer is required as a test. If we don’t get the answer right, there is no second chance. When we design, there are stretches of exploring, ideating, imaging, and iterating design possibilities, then going back to look at other ideas. Rarely do we pop up with a surefire design the first time.

Design is not a multiple choice test: ‘C’ may not be the only answer and the possibilities are many times greater than ‘all of the above’—there are many ways of problem solving with each project we tackle. So, playing around is a way to explore many ideas in a low risk atmosphere; according to the Root-Bernsteins play strengthens many of the mental skills we engage when we are creating (1999). When you are playing around, not every cracked egg has to be scrambled.

Still Curious? Good! Curiosity is a precursor of exploration; it stokes the fires

of creativity.

Check out these resources from a library near you:

- Robert and Michelle Root-Bernstein’s Sparks of Genius: The 13 Tools of the Word’s Most Creative People (1999)

- Mitchel Resnick’s Lifelong Kindergarten: Cultivating Creativity Through Projects, Passion, Peers, and Play (2018)

Marianne Cramer is an Associate Professor at the College of Environment + Design. She currently teaches contemporary landscape design theory, and first year undergraduate design studios. Prior to her academic career she was responsible for the plan to rebuild New York City’s Central Park and a coauthor of Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan. She was instrumental in strategizing the management plan for the woodland areas of the park and introduced adaptive management strategies. She was also responsible for the design of the landscape surrounding the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Central Park and oversaw the design of other Central Park landscapes. Originally from western Pennsylvania, she grew up on a dairy farm and threw around a lot of bales of hay.

education

MLA, University of Georgia (1977) Research Thesis: The Role of Feedback in Design Systems

BA, Biology Thiel College (1969)

Research Interests

Professor Cramer’s research focus is in the area of design thinking; identifying cognitive skill sets necessary to problem-solve, create and innovate; and coaching the practice of those skills in first-year design studios. She is also interested in identifying habits of embodied cognition that are useful for design students to embrace and practice—of which she describes play as one of those habits.

Her current research project looks at a century of publications in her disciplinary field to explicate the development of procedural theory and the swing from cognitive skills to staged process models as guides for design process. Because of the explosion of brain science research, she is advocating a swing back to emphasis on design process—the how, rather than a singular focus on the products of design.

Thesis and dissertation topics of interest include design studio education and pedagogy, cultural landscapes, park planning, design and management, adaptive management, design history and theory, cutting edge design research exploration.

Selected Publications

- Firth, Ian J. W. and Marianne Cramer. 1999. “Ecosystems and Preservation: Learning from New York’s Central Park” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology 30(1)15-20. [Journal cover illustration]

- Putnam, Karen and Marianne Cramer. 1999. New York’s 50 Best Places to Discover and Enjoy in Central Park. NYC: City & Company.

- Rogers, Elizabeth Barlow, Marianne Cramer, Judith Heintz, Bruce Kelly and Philip Winslow. 1987. Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan. Cambridge: MIT Press.