Tucked away in UGA’s west campus sits a small, neglected spot of overgrown woodland called People’s Park. The area may not be impressive today—in fact, most people probably would not even recognize the rather unkempt landscape as a “park” at all. However, its history highlights the ever-changing relationship between the UGA community and the citizens of Athens, and the important role that urban open spaces play in both symbolizing and advancing social equity and justice. CED Professor Eric MacDonald and Master of Landscape Architecture student Gretchen Bailey are working to uncover these aspects of the park’s history.

In the early 1970s, student activists from UGA established People’s Park as a show of solidarity with nationwide social protest movements, which included resistance to America’s involvement in Vietnam. Though more research must be done to be certain, the students were likely inspired by the first People’s Park created for similar reasons by students of the University of California, Berkeley a few years prior.

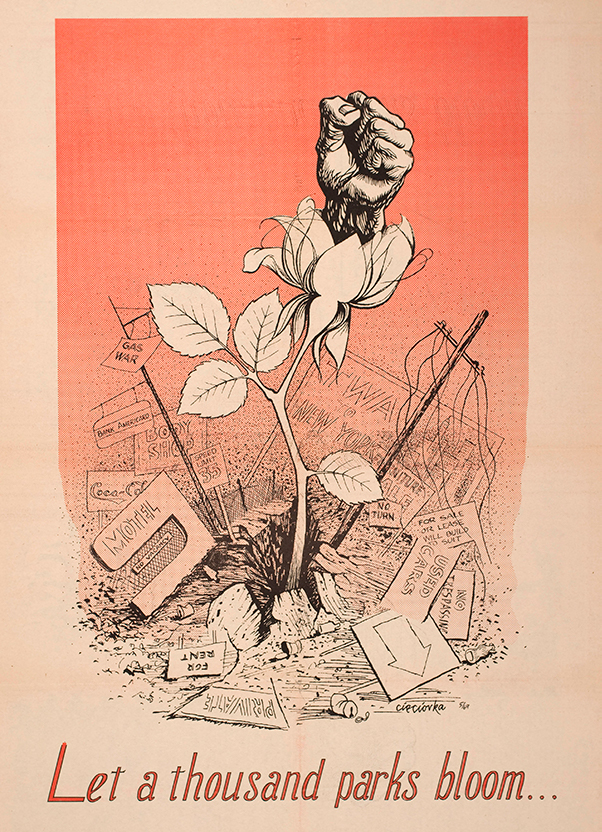

A poster for the People’s Park established at UC Berkeley in the 1960s.

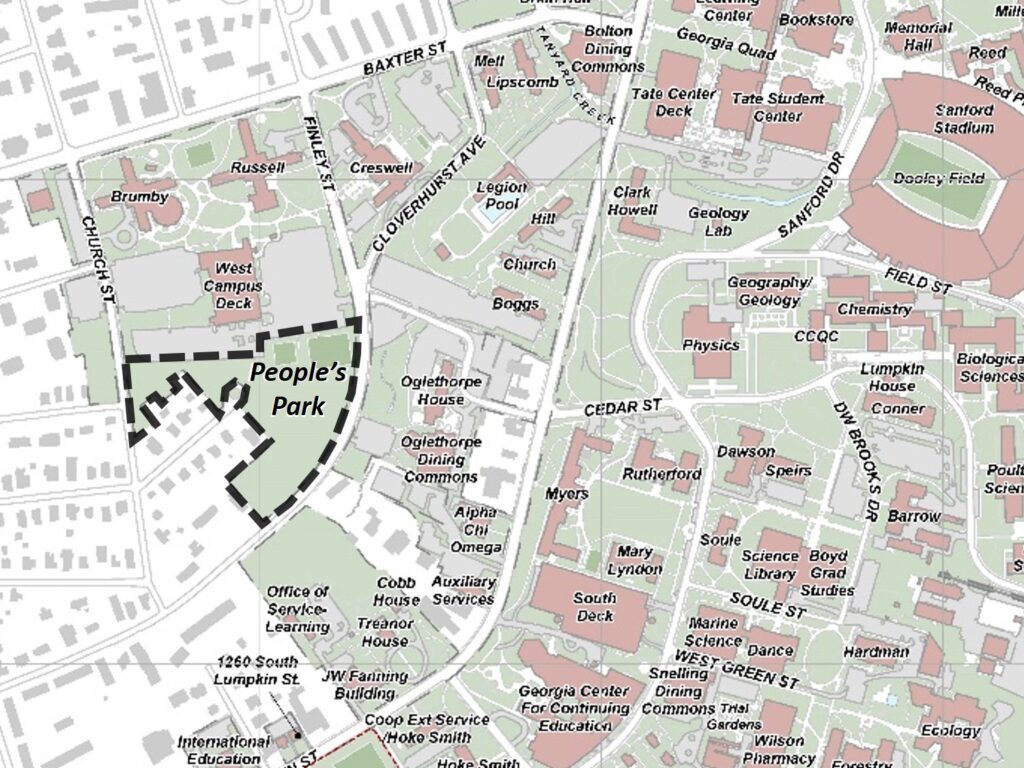

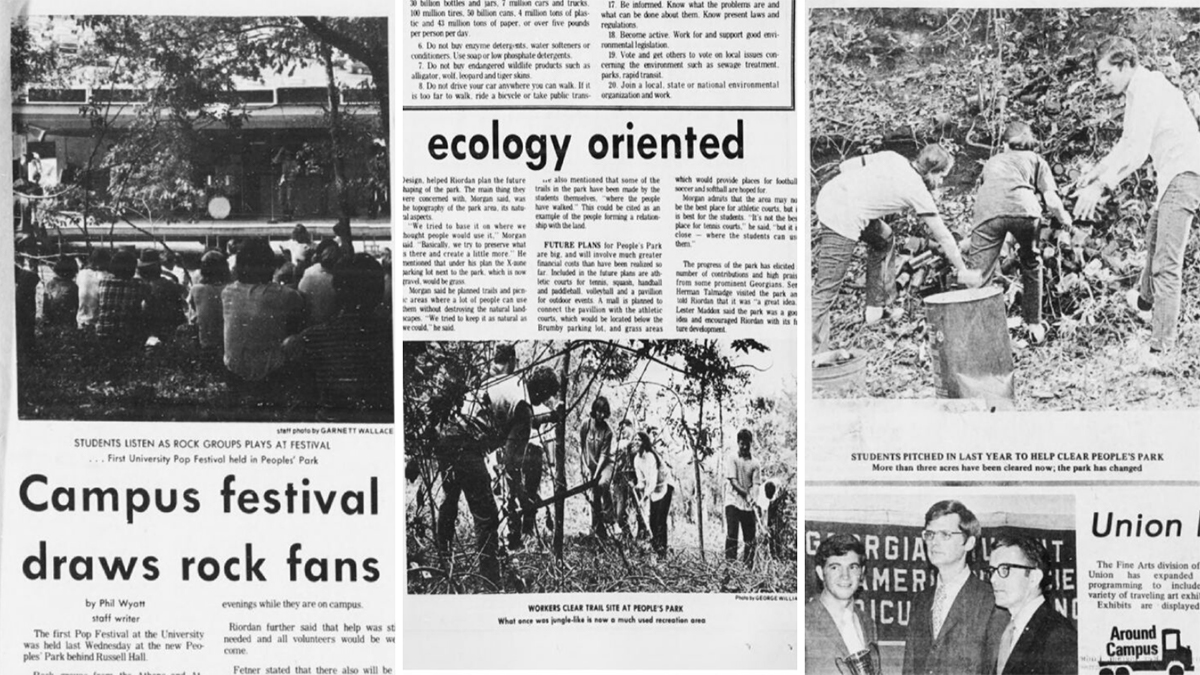

Located on Cloverhurst Avenue, east of the West Campus Parking Deck and across the street from the Oglethorpe House dormitory, the park’s placement is no accident. Students created People’s Park shortly after the opening of the “high-rise” dormitories—Cresswell, Russell, and Brumby Halls—to protest the encroachment on open spaces by new campus construction and promote the establishment of more public green spaces. CED students participated in the park’s design and construction, which included trails, new plantings, a stone-lined bonfire ring, and a performance space for rock-and-roll concerts.

MacDonald modified this map of campus to include People’s Park. The fact that no campus maps show the park is a sign of how little known it is today.

The park’s placement is doubly meaningful: the park occupies part of the southern border of Linnentown, a predominantly African American neighborhood that was removed as part of an urban renewal project in the 1960s. In 1962, the city of Athens, exercising its power of eminent domain, worked out a deal with the University to expand campus to compensate for increased enrollment. Further research is required to determine whether or not the park’s originators were aware of the displacement of the Linnentown residents. Nevertheless, the area’s history reinforces People’s Park as a dissent against further development and a symbol for social justice.

These clippings show the commitment the park’s founders had for the space as they volunteered their time and socialized.

Although her research activities are currently constrained by University closure, social distancing guidelines, and restricted access to archival collections, Bailey is working diligently to capture the history of this little-known corner of the UGA campus. UGA Special Collections archivist Mazie Bowen as well as Janine Duncan, historic preservationist for UGA Facilities Management Division Grounds Division and CED alum, have been aiding Bailey in her research.

Gretchen Bailey, MLA Student studying the history of People’s Park.

Though her research is still in its early stages, the story of the park she is writing relates to the current conversation about racial and social inequality. The research raises questions concerning the politics of claiming and occupying urban space, the agency of who can and cannot be heard publicly, and the struggle for equality.

People’s Park is just one of the many “naturalized spaces” defined by the UGA campus master plan. Most of these spaces receive little landscape management. MacDonald hopes that research like Bailey’s will bring greater attention to these spaces and therefore gather support for their restoration.

People’s Park is a designated “naturalized space” on the UGA campus. Over the years the park has become overgrown and unkempt, making bonfire rings like this one unusable.

Since 2014, MacDonald has included People’s Park as a stop on a field trip focused on the hidden histories of campus landscapes. MacDonald and Bailey hope that a web-based platform can be created to communicate the histories of campus environments and bring attention to People’s Park and other naturalized spaces such as Driftmier Woods and Tanyard Branch.

Illuminating the history of People’s Park and similar spaces is essential in understanding the history of campuses and the cities they call home. Moreover, understanding the intended purpose of spaces like People’s Park helps designers participate more actively in national conversations concerning citizen-driven initiatives to preserve open spaces around the world.