In the wake of UGA’s online instruction, Brad Davis, Associate Professor at the CED and MLA coordinator, came up with a clever workaround for his elective class, Plants for Temperate Landscapes, which is open to undergraduate and graduate students. During a typical semester, the course involves a number of walking tours in and around Athens and instructs students to identify unique trees, shrubs, grasses, vines, and perennials, including native and introduced vegetation.

UGA’s mandatory online instruction forced Davis to think outside the box about how to provide his students with a similar experience despite not being able to lead in-person walkalongs. In the end, Davis chose to lead live video plant walks, giving his students an approximation of a typical walk and highlighting notable plants along the way. Through this series of videos, narrated and shot by Davis himself, Davis takes specific walks both on and off campus, turning his camera on plant specimens and dropping tidbits of knowledge while conversing with his students.

Notable locations for the walks include UGA’s North Campus and the Founders Garden as well as locations outside of campus such as Athens’ Five Points neighborhood and the Georgia Botanical Gardens. Dr. Michael Dirr, a titanic figure in the land arts, fortunately lives in Athens and regularly makes his own garden available for student walkthroughs. Though he retired in 2003, the former horticulture professor and Director of the UGA Botanical Garden remains active in research and new plant development.

This elective course is not required for any major program, and students are “keenly interested” in the material. The goal of the course is to expose students to between 200 and 250 species not covered in the official CED curricula.

Professor Davis turns the camera on himself.

In the videos, Davis travels along the walk exactly has he normally would. He identifies plants and notes specific characteristics to train students to identify plants independently. This semester, the response to the course has been as positive as ever. Students appreciate the time and effort put into Davis’ videos.

Of course, modifying the course so drastically was not without its drawbacks. The largest negative consequence of the new online plant walks is the “separation of the lens.” While it is possible for video to give viewers a detailed look at plants and animals—programs like Planet Earth are proof of that—amateur videography shared over a live-streamed video conferencing platform is an unideal way to introduce viewers to new species. Even if Davis was able to capture and present professional-quality video, studying plants through a screen is a poor substitute to seeing them in person.

Davis states that “even during a typical semester on campus, students often make the mistake of studying for field identification exams by simply perusing Google images. Searching online can be very misleading even if the images are correct, as there is often some level of genetic and morphological variation within even one species, in addition to differences in appearance caused by other factor such as age, light exposure, and health.”

Davis had to change not only the methods of instruction, but also methods of testing. The question of how to administer exams has plagued educators since online instruction began, but Davis devised a testing strategy which seems to have solved many potential issues and opened the door wider to lifelong learning.

For final grades, Davis charged his students with creating their own plant database, not unlike the database maintained by the Missouri Botanical Garden. Davis told his students to discover new plants on their own and conduct their own research. They would then take what they learned to compile a compendium of newly discovered local plant life.

As a result, students ventured into their own spaces and made their own observations based on the groundwork laid by Davis in his walkalong videos. In a way, this project mitigates the issue of students relying on presentations and online material to learn about diverse plant life. Davis stresses the necessity of surrounding oneself with living, three-dimensional plants in order to solidify plant knowledge and gain an understanding of the way plants change over time. By making students create their own database, Davis hopes that students become self-led lifelong learners with the ability to add new plants to memory.

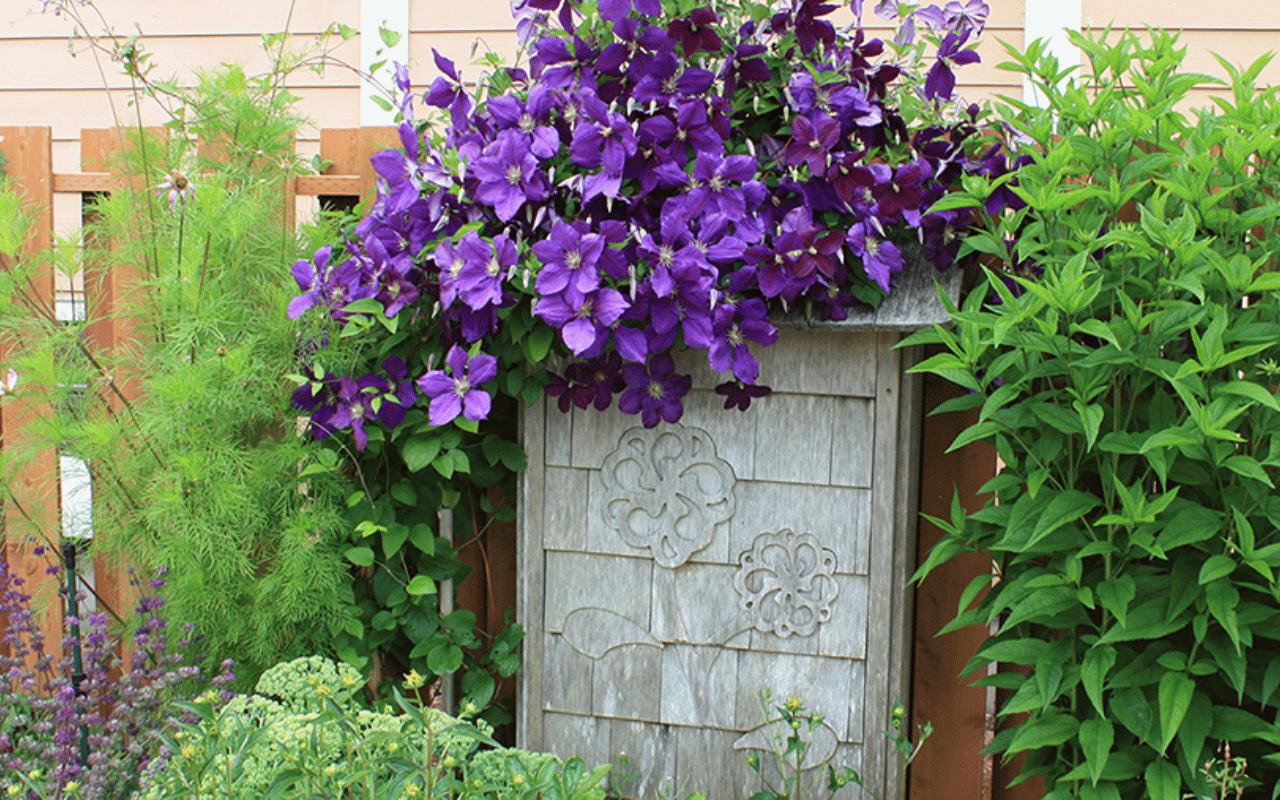

The Clematis is just one of the plants that Davis examines during the plant walks.

The ability to become familiar with local plant life is important for landscape architecture students as they graduate and take jobs in new regions with a completely different climates and plant palettes. Davis shares from his own professional practice experience working in a variety of climates such as tropical south Florida and the mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. “The second plant palette can be learned much faster than the first – you learn what patterns to look for and many times the plant family or genus is the same, with new species occurring in the new region.”

Davis is just one of many faculty who have adjusted their typical teaching methods in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. For more stories on faculty, staff, students, and alumni who have responded to the coronavirus in unique ways, visit the CED’s Our Response to the Coronavirus page.